Irina Aristarkhova

I have good news for you: we still deliver miracles,1 after all… After the comfortable, transparent and always-already anti-Western, antimen or generally oppositional rhetoric that has over-determined our practices and discourses; After unrestrained quotations that mimic without subversion or local appropriation fashionable Anglo-American and French poststructuralist and postcolonial figures; After being consumed by antipathy towards anything not ‘ours,’ that is negated or embraced in accordance with the logic of sameness; After being taught how to compete with each other under a “phallic” sun without respect for female genealogy, continually denying feminist history and the radical creativity of our fellow-women; After being left without feminist education, theory, ethics and aesthetics as part of our curriculum, and still not teaching it when we have an opportunity; After “cutting off the tree branch on which we sit” by reproducing jealousy, ignorance and disrespect towards other women’s achievements; After having no positive articulations of/for the word “woman” and for women in our lives; After having no mediators for professional long-term and short-term relationships that would still leave a space between us to breathe and to create in all our radical otherness among ourselves; After all that has stood between you and me. As you may have noticed by the preceding statements, I am by no means unaware of the obstacles that surround us and surely cannot be blamed for being “too optimistic” about doing feminism in, so-called, “non-Western con – texts.” It is exactly this measured caution that leads me to consider the enactment of any complex and fruitful professional relationships between us as an engendering of miracles, where we co-evolve a new language, new art and new writing, that many other women can partake of (and happily, they do—sometimes acknowledging us, sometimes not). Here I would like to share with you two of my constructive and happy engagements with women artists in Singapore, presented in the collaborative form in which they developed.2

AN ART OF COLLABORATION: AMANDA HENG

Amanda Heng is arguably the most well-known and persistent feminist artist in Singapore who in the course of many years has tried to introduce a critical feminist agenda into the Singapore art scene. Though I had heard about her and had seen her art works before, we first met at the symposium on feminist art that my colleagues and I organized at an art institution in Singapore. The symposium it – self was a result of a graduate workshop and an exhibition on feminist art entitled, “A Self of One’s Own” that I conceived and curated in 1999.3 Amanda Heng’s serious commitment to collaboration among women of different perspectives and views was clearly evident even in this first encounter. For Amanda Heng, to be a feminist means “to be aware that women are still in the position of being dominated by gender stereotypes,” and to be aware of “a patriarchal construct that functions to limit our experiences, expressions and expectations of the lives we live.” It means “a conviction to express women’s oppression, to investigate, explain and analyze the causes and consequences and to seek new possibilities, strategies and relationships for liberation of women’s personal and political life.” She admits to having been radically transformed by feminism. She says, “Feminism has made very im – portant contributions to contemporary cultural discourses by proposing alternative points of view to phallocentric thinking. It has been basic and fundamental to my discovery of myself as a female person. It gave me confidence to accept myself as I am and helped me realize that my lived experience as a woman in my own terms is important and valid. I find feminist thought liberating because of its diversity, vitality and its refusal to stop changing and growing with time. More importantly, it permits each and every woman to think through her own thoughts and set herself free.” For me, to be a feminist, means to learn about women’s cultural histories and celebrate women’s creativity around the world, in order to try and reverse the language of oppression into a language of fecundity and inspiration. The persistence of the image of women as an oppressed group (though I do not deny the existence of sexist oppression and discrimination on a day-to-day basis) seems to me complicitous with a perpetuation of masochistic trends within women’s culture that adds to their anger and unhappiness. Alternatively, I believe, the challenge lies in the following questions: How to invent and introduce alternatives, embodied and embedded in our everyday life, that would provide women with building material, both theoretical, aesthetic and psychic, to materialize happier ways of being a woman, relating to women and to men? And here our collaboration is essential.4

Amanda Heng persistently addresses issues of the social and cultural position of women in her works and her artistic practice that draws from a strong sense of the history of women in Singapore, particularly colored by the experiences of the women in her own geneaology. She says,

For my grandmother’s and mother’s generation who came to Sing a – pore from China in the 1920s and ’30s, women had only one life, that is to serve their husbands, have children, look after their households and work as unpaid laborers for family businesses. In that generation women worked their whole lives without pay. Their only hope for better lives was their children. Many Chinese women looked for life-long security and became amahs or maids in rich or British families. They lived and worked as a member of the families until they were too old to work, and then they would return to China before they died. Salaries were sent back to China to support their families. Some remained single throughout their whole lives, and others depended on their luck to get married in Singapore or China, usually becoming second or third wives or mistresses because of their low status.

The postcolonial period in Singapore’s history saw an unprecedented rise in social and economic developments that radically changed the lives of women here. While acknowledging the real changes in women’s lives, Amanda has struggled in her art to point to some of the contradictions within these newly acquired social positions. For example, she notes that the developments in the lives of women in Singapore have been enabled by a displacement of their tradi tional roles and tasks to some other economically underprivileged women from Southeast Asia:

Amanda Heng: “Let’s Walk,” performance, 1999

The educated middle class became the dominant workforce in businesses, industries and technologies. Women enjoyed equal opportunities for education and employment not because the government respected the rights of women here but because it recognized that they could not afford to ignore half of the much-needed female work-force for economic development. Women have gained financial independence and have more choices in life generally. Today women are seeking not just economic independence but also personal meaning, satisfaction and identity from their work. Women are also expected to fulfill their social responsibilities in the reproduction of population to replace the fast graying population. Women found themselves in a difficult position to take on multiple roles. In many families, household chores and child-raising tasks are now relegated to cheap domestic help imported from countries of different cultural backgrounds. These domestic helpers from Indonesia, the Phil ip pines, Sri-Lanka, Myanmar & Pakistan are not provided life-long security, like my grandmother’s generation; they work on a contract basis under very strict rules and regulations for little money. Glo bal i za – tion and the new eco nomy have changed the relationship between employers and employees and projected exciting prospects in life for all, but the welfare and the fate of these workers in the domestic arena have remained unchanged.

There are women from all over Asia working as live-in maids in local and expatriate families in Singapore, and the very important question of how and in what ways a community of women artists can address and reflect on such issues is rarely discussed. Amanda Heng is one of those very few artists who questions the exploitative attitudes in relations among women, thus exposing the complicity between economic structures and patriarchal structures. Her cur rent work in progress focuses on presenting some of her views on the situ – a tion of domestic maids in Singapore. Her works—predominantly perform – ances, installations and videos—have always sought to engage the wider community, thus following a long feminist tradition of political engagement and its focus on raising public awareness. Many of her previous works have sought to bring critical attention to various aspects of women’s lives and exper – iences. It is noteworthy that Amanda Heng has established a name for herself in the international art scene, having shown across Europe and Asia, and undertakes as many projects overseas as she does locally. In the Singaporean art scene, where many seem to have a skeptical or, at best, cautious attitude toward feminism, I found Amanda Heng to be the only one who throughout the years has consciously taken a stance both as a woman artist and a feminist, and refuses to give up on opening up doors for collaboration. It created numerous problems for her in terms of funding, relations with other women artists, with men artists, and with the mainstream art world in Sing a – pore as well—a not unfamiliar picture to many. However, it is her commitment to holding herself open to collaboration, to difficult questions of art theory and contemporary art practice, to society and its problems, and to welcoming differences between us, that have made her into one of the most active and critical artists in Singapore.

Judging from my other experiences both in Singapore and Russia, I can affirm that the most welcoming and engaging of artists are those creative women who have thought, learned, and worked through their relation to a heterogeneous feminist heritage, and/or who are still searching and ready for highly complex theoretical and aesthetic negotiations. Margaret Tan Ai Hua, another woman artist from Singapore strongly committed to a feminist agenda says: “The fact that the term ‘feminist art’ or ‘feminism’ was coined in the West does not mean that we in the East should reject/oppose it. Of course there was also consciousness among our foremothers here, and, in fact, the concerns might be the same as their Western counterparts: The role of women in a patriarchal system and the need to question such an allocation. I have no problems with the terms and I see the squabbles of East versus West, who became aware first, etc., a waste of time and energy. Patriarchal views and practices are still so predominant both here and elsewhere in the world, we should be more focused on empowering each other, to make a change in the system and ourselves.”

Margaret Tan here seems to be responding to dominant oppositional attitudes toward both men and Western feminism that one often hears expressed in forums that address the position of women in Singapore. There are clear similarities in this aspect to my experiences in Russia, where very often our feminist discussions do not extend beyond criticizing men or social constructions that make women into sexual objects, and Western feminism for being “too Western and too wealthy” to be applicable to women in Russia. However, those given the privilege to speak during such occasions, rarely reflect on their own complicity in perpetuating hierarchical attitudes towards women around them, especially when it comes to class, ethnic or religious differences. Such anti-men or anti-Western rhetorics often serve as claims to truth in our cultures, or as ethical justification, which in fact, works against the critical re-valuation and re-working of alternatives to the hier archical (and hence, still phallocentric) frameworks within which women in positions of power (teaching, inviting, curating, distributing) speak and act.

A Women Artists’ Registry meeting

Amanda Heng has been teaching art students a workshop on “Col lab ora – tion.” Collaboration, a welcoming of differences, is especially strategic for wom en artists: Learning how to respect and expect each other’s otherness, to safeguard borders of creativity of one self, to leave a space for the creativity of the other. The question of collaboration and coming together without draining each other of energy and inspiration has been central to feminist debates for decades. Amanda Heng’s conviction that it is only in being “together” with all our differences that we can leave a permanent, long-term impact, and her willing ness to en – gender diverse collaborations has been crucial for our professional contact, and more importantly, for seeing a miracle of embodied new collaborations of women artists in Singapore who often do not share the same frames of reference.

As an example of Amanda Heng’s ideas of collaboration it is useful to mention one of her latest projects which is also symptomatic of her long-term engagement with the history of women’s art. With the help of other women artists, she organized a “Women Artists’ Registry” that primarily targets Sing – apore and potentially other South-East Asian countries. The meetings she organized in her art studio to launch the Registry were the first coming together of many prominent women artists practicing in Singapore, who came despite their differences of opinion and cultural experiences. Some of the artists, like Amanda herself, share a feminist agenda with awareness of their position, while others expressly refused the feminist label or agenda. The Registry interestingly gives the space and opportunity to negotiate these differences without having one dominant point of view. Amanda’s work on this Registry stirred some controversy among certain men artists working in Singapore who suddenly discovered that they were in fact, male artists and not artists, in general, anymore! Because of Amanda Heng’s international recognition and associations, this Registry promises to serve as an important point for documentation and institutionalization of the thus-far ignored contributions of women’s art in South-East Asia.

On a few occasions Amanda Heng voiced an argument that I deeply share: Unless we, in our own local contexts, create a theoretical web which is both aware of international heritage even while radically localizing and histori – cizing it, women in non-Western countries will be left without “A Self of One’s Own.” And to this end, the issue of collaboration is crucial, but it has to work both ways: There must be a you there, a committed you, a you-she with desire for an ethically inflected relationship of sharing, for our collaboration to happen. However, this last point is extremely complex. Women have been historically habituated to situations where they learn of necessity to form personal networks of survival which are rather inimical to open-ended pro – fessional inter-subjective relations with fellow men and women alike. The groups that result from such emotionally effected ties often lull them into complacent states of feeling comfortable and safe, sometimes to the very exclusion of other dimensions that are always necessary for creating new spaces and languages. We are still often left with bitterness and grim questions as a result of our failed attempts to collaborate (by failure I mean jealousy, plagiarism, disrespect, stagnation, emotional distress, instead of feelings of growth, fulfillment, happiness and movement). Maybe we must learn how to be separate, to have borders that leave some air for those who would like to share this air with us, respecting their borders too. And the notion of woman that we engender by happy collaborations changes together with those localized strategies of feminism that women artists like Amanda Heng create, together with others. It is exactly this notion of “woman” that I will try to engage in the pages that follow.

ART MADE BY A FEMINIST: SARASWATI GRAMICH

A radical change in the notion of woman and our re-appropriation of that notion and others, is at the core of my fruitful engagement with the work of Saraswati Gramich. She is a lecturer and a practicing artist, currently residing in Singapore. Her view on being a feminist is closely tied to her art. It means, she says, to challenge a number of discourses: The hermetic view of scientific inquiry as it was challenged by Donna Haraway, when she suggested that objectivity means ‘situated knowledge,’ instead of transcendence of all limits and splitting of subject and object. Luce Irigaray who envisages “a culture of differ – ence” between men and women, and opening up a space that allows creativity and mutual inspiration.

Saraswati Gramich’s art is concerned with the issues of order and chaos and their aesthetic embodiments, and she researches extensively questions of the history of science, chaos theory and general issues in contemporary art. She says that she tries to question “the definition of objectivity in scientific methods” and “the binary logic in Western tradition, such as good/bad, order/antiorder as chaos. Also questioning what is good/strong art and bad/weak art, men’s art/women’s art, etc. Traditionally, these have been regarded as opposites. But, chaos theory, and feminist philosophies, have re-evaluated these views radically. Chaos theory explains that not-order is also a possibility, distinct from, and valued differently than anti-order. It explains that chaos may either lead to order (through a self-organizing system), or it may have deep structures of order encoded within it. In both cases, its relation to order is more complex than traditional Western oppositions have allowed.”

Saraswati Gramich, “Self-Organization,” Installation, 1999

The important question that Saraswati Gramich’s work challenges us with is why the notion of woman artist or “woman’s issues” cannot be redefined to be wider than, not just inclusive of, humanity at large. Why could it not be two humanities, at least two? For only by having at least two, can we have some kind of encounter. Otherwise, we fool ourselves about meeting each other; if we are all the same and thus can be dissolved by one there is no possibility of encountering some/any other. The issue here is of creating a space for general and transcendental dimensions of female genre (not resting on such fashionable and still reactionary notions like ‘excess,’ ‘subtext,’ or ‘remainder’) a thinking about woman-kind that is not restricted to a masculine human, but rather transcendental also, though different from it. Having its own relation with spatial and temporal dimensions of generality and particularity of the female being, as proposed by feminist philosopher Luce Irigaray. Thus I see the radicality of the works of Saraswati Gramich in her awareness of the necessity to create alternatives to masculinized notions of chaos, order, space and time, and even implying a different approach to the questions of transcendence or God. However, her positioning of herself as a feminist tends to provoke questions about how her art can be related to the question of gender difference if it is embodied in supposedly gender neutral installations and paintings, that seem to have nothing to do with “women’s issues.”

When considering the question of the definition of feminism, and especially feminist art, it is important to stress that it is more productive, as art theorist Selma Kraft suggested, to work out a feminist definition of art instead of a definition of feminist art. I think feminism seeks to identify, reflect, and act upon the social, cultural and political conditions of women’s lives, where even the category of “woman” is not taken for granted. Let me explain why we cannot take the category “woman” for granted by deliberating on the label, “woman artist.” Let us start with the comment of one student about works exhibited in “A Self of One’s Own” that responded to the theme ‘space.’ This student felt uncomfortable about Saraswati Gramich’s installation being there, because he said it does not seem to “look like lady’s work,” but rather like… and he hesitated for a moment. I then completed his sentence by asking “men’s work?” He was obviously not happy with this definition. After trying to find a way to describe the work, he said: “It looked to me not like a woman’s work, but rather ‘normal.’” I am not sure how much “normal” also meant “neutral” for him, but his unreserved sincerity provides us with a useful introduction into the conditions under which women artists find themselves.

Normality and gender-neutrality of men’s art is taken for granted. When men produce works with reference to space, spirituality, the universe, human existence, or sexuality, their gender does not seem to be an obvious part of the creation process. Until recently our art history had practically no references to women’s art, making it gender-blind. Women artists were so invisible that female students often did not even ask themselves what had already been done by women artists before them: It was simply not there. And given the preju – dicial exhibition and curatorial practices of the past, many aspiring women artists had very little chance of coming across works by critical women artists. Thus, the masculinity of the artist disappeared as an incidental element of art making. However, what made the student who commented on “lady’s art” feel uncomfortable about calling men’s art “normal” is exactly what demands the widening of the notion of woman, such that it necessarily includes interests in space, spirituality, or the universe. Saraswati Gramich’s work displayed in a feminist art exhibition nudged one to question the gender neutrality of men’s art that hides itself behind notions of “human” and “normal.” By making works on space, and on order and chaos belong to feminist art, Saraswati forces the notion of “woman” to be wider than our presently narrow notion of “hu – man.” With this gesture she teases the man out of the ‘human.’

Responses to feminist art are often expressed through the insecurities and anxieties of the mainstream art establishment that suddenly finds itself guilty of having represented mainly men artists as if they represented all of hu manity. I will exemplify my point on another level. When we discuss issues of ethnic difference, we seem to agree that European art cannot pretend to represent world art, and that Western artists should not pretend to be culturally neutral, devoid of a particular cultural and historical background. Their relation to spirituality, body, space, and time might be specific to their training and upbringing but that, of course, does not mean it is not valuable. However, in the case of sexual difference, many still insist that gender does not matter in issues like space and time or order and chaos. Moreover, the surprise in seeing Saraswati’s work in relation to feminism can be read in at least two different ways. First, that feminism can only be about those things that the category of “man” cannot be: Giving birth, PMS, etc. and, thus, the category of woman is reduced to that which is “not-man,” depriving her of an identity of her own. As a result, if she takes on issues of space and time, she must stop being a woman, she must switch herself off and become an ‘artist,’ that is, try to become or mimic the art of men, since feminism has nothing to do with space and time!

Second, such a reading is uninformed by the fundamental nature of this primordial opposition between male/female in our cultures. “Order” in major philosophies and religions around the world has been associated with the so-called “male principle” while chaos has been labeled ‘female’. Many other oppositions and combinations have a direct relation to such reasoning: Mind/body, purity/impurity, good/evil, reason/instinct, etc. Feminist interventions into such oppositional categories are meant to redefine the way we think about ourselves and the world around us. This project seems to be much more complex than stereotypical notions of feminist art and women’s issues, and one of the reasons I see it as radical. However, it is necessary to stress that this project is in tune with contemporary philosophy and art. This project is also part of an attempt to think outside the comfortable split of people into white and non-white, or civilized and non-civilized. Constructing a self of one’s own for a woman is a long path, since the very category of “woman” has been so restricted, but it is worth it, and there is an urgency for it.

Saraswati’s work also has been sexualized and dismissed as “too beautiful” by some critics and artists. Her insistence on aesthetic qualities and balanced attention to the material and compositional sensibilities often go against the grain of what is considered a strong artistic statement in contemporary art, both by “riot girls” and “bad boys” in the art world. She says: “Many times my artworks are criticized as ‘too beautiful.’ One art critic said, ‘Wonderful work. My only criticism is that the work is too beautiful. In the paintings and drawings there is an exquisite refinement particularly in color. This tends to undermine the work as it veers too close to the sensibilities of the fashion industry and décor.’ It seems to me that the ‘definition’ of good art is still coded. Isn’t beauty also a possibility?”

Thus exquisite refinement in the work of a woman artist, taken together with transcendental questions, is seen as disturbing and, hence, asking for im – mediate appropriation of it or resolution within some habitual and readily available framework like “too beautiful,” “too sensitive,” “not strong enough,” that is, somehow and somewhat “tooo much.” This unbearable nature of beauty and refinement in works supposedly not relating to a women’s agenda is of particular interest to me in Saraswati Gramich’s work, since I am trying to think of the inspiration and positive alternatives that we want to create in women’s culture and for female-kind. The subtle sophistication and complexity can help to play at the border of both dangers: Of essentializing the woman artist and women’s issues, on the one hand, and of draining away the positive energy associated with “angry art,” on the other. Her art questions comfortable restrictive definitions of women’s issues even for many women artists themselves who prefer to see such issues as outside of more general or “non-women’s” questions of order and chaos, or space and time.

Even though it is not readily apparent in her works, Saraswati Gramich also reflects a strong concern for the immediate social condition of women in her home country, Indonesia. She writes that the main problem for women is a lack of information on sex education, including sexually transmitted disease, contraception and abortion: “Lack of information on sex education causes many young women to be abused sexually, sometimes clandestinely. Many young women are harassed on the street by individuals or groups of boys, and live in fear of violence. Women in Indonesia have no right to an abortion, even if the pregnancy is due to a “forced” sexual intercourse. Abortion is only legal if medical doctors state that the pregnancy endangers the mother or the child. This leads to a high incidence of infanticide by young mothers.”

She also notes that in Indonesia, as in many parts of the developing (and one suspects even developed) world, there is a predominant tendency for women to undertake the responsibilities for family planning: “More women are taking precautions for contraception than men. This causes more women to have side effects due to the Pill or IUDs. I think there should be a negotiation between men and women in deciding who should be the one who takes the precaution.” Again, I would stress that very often women participate in such silent practices of “following a tradition” even when social and cultural conditions have changed considerably and the notion of tradition itself is being questioned.

It brings us back to the notion of ‘woman’ and its restrictive definition that imprisons female identity, when such notions as motherhood or intimacy are taken to be natural, depriving them of their more enabling cultural and legal dimensions. Here, two points that Saraswati Gramich thinks especially important, are to be engaged together: On the one hand, she says, “in case of vir ginity, women in Indonesia will be regarded as immoral for losing it before marriage”; on the other, “celibacy is regarded as not-woman. A lot of gossip will be spreading and buzzing around her.” Thus, actually virginity is not a cultural option, it cannot be chosen. Virginity is not considered as a woman’s choice, but rather seen as a natural condition to be preserved as a gift for husbands, but not as a ‘thing in itself.’ The same goes for the Christian tradition: Virginity is for God– husband–father, and not a socially acknowledged choice of a woman herself— for herself, or for someone whom she chooses. This dimension of legal ownership of one’s body and social status, especially in relation to husbands, is absent in Indonesian women’s lives. Gramich writes that “As in a predominant ly Mus – lim country, a lot of women have to accept it if their husbands have mistresses even without their consent (Muslim men are allowed to marry up to four wives, but only with the wife’s consent). And as a wife, she still has an obligation to serve him. The perception of a good or civilized woman is someone nice, kind, loving, enjoys serving, good cook, pleasant, simple, not argu ment ative, will al – ways support her husband from behind (in Indonesian: Tut wuri handayani).”

The relationship of a woman to her body is still largely outside legal and symbolic language, and remains so even in its translation into the language of new technologies5 (for example, the notion of the matrix). Hence it is often appropriated for the use of the “community”—children, husbands, family, their welfare and their future—like in the abortion rights debates. The issue of her subjectivity and ethics is somehow dismissed by conflating all women’s issues with the notion of the natural, meaning that they are given, and therefore cannot but be any other way. Unfortunately, even when addressed within and by women’s art, there is a tendency to enact empowerment through some natural link with earth, moon, softness, and smallness—everything, that is not-man, everything oppositional, with claims of “taking it back” from masculine patriarchal culture and its structures. I would argue differently, that there is a serious need to redraw the map of women’s issues, and how women artists might address that, and feel comfortable precisely as women-artists with a wider notion of sexual difference. In many contemporary practices of women artists, I sense the creation of a new dimension and expansion of women’s art as an embodied feminine universal, that is, interactive for both genders on the issues of technology, space, and human existence, exactly because it deals with it without collapsing sexual difference into (n)one, or into two opposites, thus allowing other differences to be acknowledged.

Saraswati Gramich, in place of the term ‘feminist art,’ prefers the expression “art done by a feminist.” She says, “personally I would like to see an acknow – ledgement of difference of interest in dealing with the issue, exploration of ideas, possibilities, space for creativity, collaboration among women and/or men. It makes me understand my standing in my artwork, culture, condition of being a creative and productive human-woman, and my position relating to human beings (men and women). Being of mixed ethnicity (Eurasian), I don’t identify myself as belonging to one specific culture/country, but as having mixed-cultural identity. My art questions the notion of chaos and order in space and time from this mixed-cultural upbringing, woman artist point of view, and visualizing an acknowledgement of difference in ideas, possibilities, and artlanguage. A feminist point of view has definitely empowered me.”

Her last phrase is very simple, but it contains all the power that feminisms have been about. And if they fail it, if they make women and men oppositional to each other and among themselves, hating each other and desperate; if they do not bring shared happiness and confidence into women’s lives; if they do not make us more respectful of each other’s differences and listen to them, then it is time to redefine our position, since it is feminism that was born to deliver miracles into women’s (and therefore also men’s!) lives. We have certain respon sibilities to the history and commitment of international feminisms, but at the same time, because of this history we have to re-learn our ethics and aesthetics.

Thinking of such historical responsibility, I have tried to highlight here two examples of my productive and happy engagements with women artists in Singapore: Through the art of collaborations, short-term and specific, benefiting from differences among us, and via a long-term investment into searching for new frameworks of women’s creativity.

1 The notion of miracle draws on the possibilities open to us despite all that inhibits or frustrates them. Following the call of Luce Irigaray to learn how to be happy, I have renamed them here as an “engendering of miracles” using two main strategies: 1) effective collaboration, and 2) radical re-evaluation of the notion of “woman artist.”

2 Of course there were, and are, many more women in Singapore with whom an atmosphere of mutual interest and respect was created, and I would like to express here to all of them my deepest gratitude, especially to my students and colleagues at work, and also to members of AWARE (Association of Women for Action and Research in Singapore).

3 The exhibition and symposium “A Self of One’s Own,” featured thirteen women artists and four scholars from nine countries. It was the result of a graduate workshop that I conducted in 1999 in Singapore. Currently, I am finishing work on a publication which documents and reflects on this event.

4 Amanda Heng has since clarified in a conversation that her position is multifaceted, and not merely oppositional, and this is indicated by her statements quoted above.

5 For examples of my cyberfeminist interventions see “Cyber-Jouissance: A Sketch of a Politics of Pleasure at ; and “Hosting the Other: Cyberfeminist Strategies for Net- Communities,” in Cyberfeminist International Reader, Hamburg, 1999.

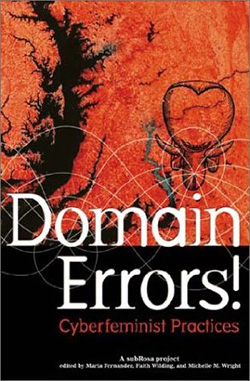

Domain Errors!: Cyberfeminist Practices

Edited by Maria Fernandez, Faith Wilding and Michelle M. Wright, « Domain Errors! Cyberfeminist Practices » is a provocative collection of essays, poems and art works that thoughtfully analyzes technology’s impact on women and suggests possibilities for radical change. The book is a project of subRosa, an organization that is dedicated to articulating a sophisticated cyberfeminist critique of society.

Domain Errors! Cultural Writing. Women’s Studies. « This exceptional collection of writings and artist projects performs a resistant feminist politics. Charting new strategies and practices, the authors imagine liberatory possibilities for our bodies, identities, and social relations in the ear of digitized networks and genetic engineering »–Miwon Kwon.